|

Codicology |

of Stanford University

15 October 2005 sculpture review

by Collie Collier

For a personal celebration, I recently visited Stanford's outdoor B. Gerald Cantor Rodin Sculpture Garden, where they have the largest collection of Rodins outside of Paris, and which also contains the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for the Visual Arts. Admittedly, sculpture is not a media which I often review, but perhaps this will be interesting nonetheless. It was certainly interesting to me; I found myself with much to say to friends later concerning the art, and as one of them put it, "Guess that just goes to show it was good art!"

Rodin must have been an unhappy and contradictory man, if his art is any reflection on his personality. Most of the sculptures we saw in the Garden were of bending, twisting, agonized looking, often half-finished-appearing human forms. The few with well-defined faces were often frowning, looked driven or haunted, or at best seemed almost apathetically resigned.

There's a part of me which wonders if Rodin was an early feminist as well. His Meditation without Arms is of a nude female figure, twisting oddly so her thighs are somewhat crossed. Her partially completed face is turned into one shoulder with an expression of almost numbed weariness. Her arms and lower legs are missing, while her body texture is unfinished.

Close by is Meditation With Arms, and here you can see the body language far more clearly. Her arms are up and crossed at the wrists as she tries to cover her face, and the painful-looking twisting of her body expresses a flinching away, a desperation to hide away and avoid the viewer's gaze. Even her crossed thighs show clearly, once her lower legs are completed, how she's trying to whirl away and protect herself from being stared at.

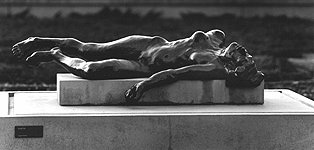

Nearby is Martyr, also a nude female form, although this one appears fallen or cast aside, as if she were so carelessly dropped that her body spilled partially over a curb, and then stiffened there. Her form is gaunt and fallen in on itself, her face almost expressionless in its smooth, unfinished pain.

Is she, and the Meditations before her, the natural result of a culture which treats women like pieces of pretty meat up for auction, to be discarded once they're no longer of use? Or was Rodin simply using the quickest and most emotionally loaded cultural synonym for helplessness, as an expression of humanity's painfully uncertain self-awareness? He was apparently an atheist -- did he fear death for the same reason, and with the same passion, as the Meditations seemed to fear visual dissection? Did he fear a martyrdom to the nothingness after death?

Victory in tragedy

The two pieces I found saddest were the Fallen Caryatid with Urn and Fallen Caryatid with Stone. I was familiar with the latter from Robert Heinlein's beautiful, strange classic Stranger In A Strange Land, where he described it quite beautifully and evocatively:

Jubal looked at the replica Caryatid Who Has Fallen under Her Stone. "I won't expect you to appreciate the masses which make that figure much more than a 'pretzel' -- but you can appreciate what Rodin was saying. What do people get out of looking at a crucifix?"

[Ben] "You know I don't go to church."

"Still, you must know that representations of the Crucifixion are usually atrocious -- and ones in churches are the worst... blood like catsup and that ex-carpenter portrayed as if He were a pansy... which He certainly was not. He was a hearty man, muscular and healthy. But a poor portrayal is as effective as a good one for most people. They don't see defects; they see a symbol which inspires their deepest emotions; it recalls to them the Agony and Sacrifice of God."

"Jubal, I thought you weren't a Christian?"

"Does that make me blind to human emotion? The crummiest plaster crucifix can evoke emotions in the human heart so strong that many have died for them. The artistry with which such a symbol is wrought is irrelevant. Here we have another emotional symbol -- but wrought with exquisite artistry. Ben, for three thousand years architects designed buildings with columns shaped as female figures.

"At last Rodin pointed out that this was work too heavy for a girl. He didn't say, 'Look, you jerks, if you must do this, make it a brawny male figure.' No, he showed it. This poor little caryatid has fallen under the load. She's a good girl -- look at her face. Serious, unhappy at her failure, not blaming anyone, not even the gods... and still trying to shoulder her load, after she's crumpled under it.

"But she's more than good art denouncing bad art; she's a symbol for every woman who ever shouldered a load too heavy. But not alone women -- this symbol means every man and woman who ever sweated out life in uncomplaining fortitude, until they crumpled under their loads. It's courage, Ben, and victory."

"'Victory'?"

"Victory in defeat; there is none higher. She didn't give up, Ben; she's still trying to lift that stone after it has crushed her. She's a father working while cancer eats away his insides, to bring home one more pay check. She's a twelve-year old trying to mother her brothers and sisters because Mama had to go to Heaven. She's a switchboard operator sticking to her post while smoke chokes her and fire cuts off her escape. She's all the unsung heroes who couldn't make it but never quit."

I can still get a little teary-eyed at Heinlein's prose. Seeing the actual statue in person, however, was far more moving than I'd expected. As Heinlein noted, both caryatids have fallen under the weight of their burdens, yet both still mutely, patiently struggle on without question. Do they already know the uselessness of complaint, the injustice of the demands with which social convention has saddled them?

Eyes downcast, faces weary with resigned acceptance of their unfair lot, they simply shift themselves to suit the impositions of others; one wadding up a bit of her draperies to pad the rough, heavy stone weighing down her smooth body and forcing her head to one side, the other tiredly resting her head on one arm as she still supports the beautiful, unwanted urn on her shoulder.

There's one other sculpture of women I wanted to mention regarding Rodin and feminism, although this one is inside the rotunda rather than out in the garden. I can't remember the title, which frustrates me, but it was something lovely and evocative like The Whisper of Earth (or was it rumor, not whisper?), and it was of two nude women. One is fallen on her back with arms flung outward, almost broken looking in her loose-jointed sprawl. The other crouches by her, arms loosely wound about her, holding her close. Her head rests against the fallen woman's head in silent sympathy with her agony.

It's only after you've looked for a while that you can trace out the faint impression of long primary feathers lost and scattered on either side of the fallen woman... and it reminded me poignantly of a quote from Kate Chopin's disturbing, fascinating book The Awakening. In it an older woman quietly warns a younger one, who is first uncertainly starting to realize self-awareness as an individual, rather than a perpetual life sentence as some man's wife, servant, and breeder:

The bird that would soar above the level plain of tradition and prejudice must have strong wings. It is a sad spectacle to see the weaklings bruised, exhausted, fluttering back to earth.

In Chopin's tragic story a freely chosen, self-aware death becomes preferable to a life of comfortable, mindless slavery. What gloriously inspiring goal did Rodin's fallen woman long for, grow wings for? Is the crouching woman like Chopin's older woman, offering comfort and encouragement? Or is she instead a loving but fearful ball and chain; or perhaps another slave grieving over her lost life, where another dared to attempt and die?

The sweep and curve of the bronze shapes draws the fingers to questioningly touch and stroke, as much as it draws the imagination into an almost fearful wondering of what inspired such horribly beautiful pain.

The despair of Hell

Back outside, and stepping past the caryatids, you find the Three Shades, a larger than life grouping of three identical nude men. They stand, heads mutely bent with despair or the weight of the entire universe resting on their shoulders, caught in mid-stride towards each other in a half circle. Each has one arm extended forward, pointing loosely as if to severely indict, or to grasp at something they know they can never reach.

They show more of Rodin's characteristic style, such as his use of one human form repeated several times for effect. They also display his odd body proportioning, where he makes pieces that technically don't match (overly large feet, or hands with missing fingers, or something similarly slightly "off") somehow integrate smoothly into a human form.

Turning, you are abruptly faced with the dark, looming Gates of Hell. They are arranged as Rodin had originally planned, flanked on the viewer's left by a free-standing, smoothly classical looking Adam, hunched over with head bowed in anger or grief, and on the right a more unfinished looking, smaller, also free-standing Eve.

Adam's torso is smoothly finished and shiny, uncomplicated and very Grecian in style but for the agony-twisted pose. It's clear he's Adam, for the fingers of his right hand are held in the same position as the famous Adam on Michelangelo's beautiful (and far more hopeful) Sistine Chapel ceiling, where Yahweh touches him with the spark of life.

Across the gates from him, Eve is in another classic pose -- the hands-up-to-the-averted-face pose Michelangelo did for the expulsion from the Garden of Eden. This sculpture has a far more unfinished look to it, which I wondered at until it was explained by the guide. Apparently a very smooth, classical, finished look was, to Rodin, unacceptable, as it reflected light very evenly and smoothly, and did not challenge the viewer to consider at all. A less smooth, more stippled effect causes light to ripple and pool in unexpected shadows and depths. Rodin considered this more unsettling, more mentally challenging to the viewer, and preferred it.

I find it interesting Adam was considered straightforward and unchallenging by his sculptor, while Eve was meant to provoke and disturb, to stimulate interest and thought -- and yes, I did phrase that deliberately. As I wrote in a previous college paper titled Feminism and the Bible: examining the Christian myth of creation, I've often thought Eve the more interesting of the two, being as she was the first theologian, acted independently, took responsibility for herself, and looked out for her partner.

By contrast, Adam comes off pretty pitifully as not much more than a whiny tattletale. Frankly, under those circumstances I don't see how Adam could be considered anything but a rough first draft. If things were created in increasing order of wonderfulness (which is today generally believed), then it is Woman, not man, who is the shining pinnacle of the deity creating in its own image. But enough about Christian creation myths -- let's address modern myths and fears of extinction.

Between the two sculptures of Eve & Adam stand the actual gates. Close up, you notice the tiny figures which populate it are all classically smoothed, but if you step away a bit, the writhing effect of all those tiny figures causes that same stippled, unfinished effect Rodin so liked. The Gates are definitely meant to provoke thought -- Rodin's own theological uncertainties are graphically expressed through his sculptural choices here.

Also present in the Gates are a multitude of the figures seen elsewhere in the Rodin Garden. The Three Shades top the lintel, although they are smaller here, and have had their hands amputated. Noticing this gives a slightly shocked feeling, which I think Rodin was trying for in his attempts to demonstrate the pain and futility of life.

The Gates caused me, oddly enough, to feel sorry for poor Rodin. As the guide described to us, he was not religious. Thus his gates have all the writhing, frustrated agonies of the christian hell, but no Jesus figure above to signify the hope and release of the christian paradise. Instead, where there would ordinarily be a redemptive, promising Christ, we see Rodin's famous Thinker, one fist crammed to his mouth, his expression more evocative of the agony of indecision rather than any sort of serene contemplation. While it is purely speculative on my part, I wonder if there was more of Rodin's personal quest for meaning expressed in the positioning of the Thinker there, than any other sculpture in the Garden.

Flanking the Thinker on either side are other smaller nudes which I unfortunately couldn't see very well. Interestingly, I recognized the Fallen Caryatid with Stone in the upper left-hand corner as well. The figures in hell are themselves quite curious. In one of the columns I recognized a centaur -- what was he doing there and what was his story? At another point there was a man attempting to crawl up and over a lintel, apparently stuck part way by the lack of protuberances to cling to. His body was contorted with the effort and you could see his face on his back-thrown head, drawn in a sympathy-inducing rictus of agony, fury, and frustration.

Most curious to me were the figures on the side pillars flanking the doors. In both cases the figures on the bottom were primarily of women, usually holding and surrounded by children climbing all about them. Indeed, the women seemed to be being stepped on by the children, a few other women, and on top of them all, men climbing upwards. I found it interesting that there in the pillars and in the gates themselves, a majority of the bottom-most women appeared fairly serene or to be helping other figures, while the higher your eye went the more anguished the figures appeared, and the more they appeared to be fully self-absorbed. Was Rodin making a subtle commentary on religious aspirations -- or on the confusion and terror he perhaps believed were induced by atheistic self-awareness?

Pinnacles

Perhaps the most confusing piece is up on a slender, eight-foot-tall pillar, standing on a clearly intentional pedestal. Titled Spirit of Eternal Repose, it's of a nude male standing off balance, with one arm bent and the other casually extended. What makes it confusing is the sheer "wrongness" of it. There's nothing under the bent arm, yet without something there an actual human so off-balance would simply fall. There's nothing beyond the extended arm, yet staring carefully will show a bit of unfinished metal there on the outside of the forearm, as if something more were intended.

Finally, the legs are crossed at the ankle, which is a classic Greek sculptural convention signifying the figure is either asleep or dying -- which this standing figure clearly is not. And yet, what was there of repose or spirituality in this rather casually pragmatic-seeming figure? Even the legs are somewhat unfinished, to the extent that the guide we listened to simply informed us this was Rodin's usual contradictory, challenging, playful art style. I cannot help but wonder if that's polite guide-speech for "I have no idea either!"

And just as you find yourself wondering if all this unfinished looking art is mere artistic laziness or ineptitude, rather than an attempt to challenge and engage the viewer -- you come across the high-standing Monument to Bastien Lepage, and you see the incredible precision in brass which Rodin is capable of. Fully clothed, Monsieur Lepage wears gaiters so carefully detailed that you can see the buckles and buttons which hold them on. I don't know who the gentleman is, but he was caught in mid-movement, his hands still curled around some vanished artifact, turning in mid-stride, his face a study of mixed determination and indecision, or perhaps worry.

Googling revealed our good Jules Bastien-Lepage was a French Realist Painter (1848-1884). I wonder if he painted outside? That would explain the full smocked jacket, as well as the carelessly tossed-on gaiters, and the almost gnawing concentration in his stare. His hands could be holding palette and brush, I think... this could indeed be who the sculpture commemorates. If it is, Rodin has brilliantly captured the driven, introspective nature of the classic artist -- that of both the painter and the sculptor alike.

Copyright © 1992-2026 B. "Collie" Collier. All rights reserved.

Web site design & maintenance: Laughing Collie Productions

Contact the web administrator for any technical problems